Reestablishment of the Wiesbaden Jewish Community

The American Military Government was informed that the Wiesbaden Jewish Community had re-established itself and wished to begin its cultural work.

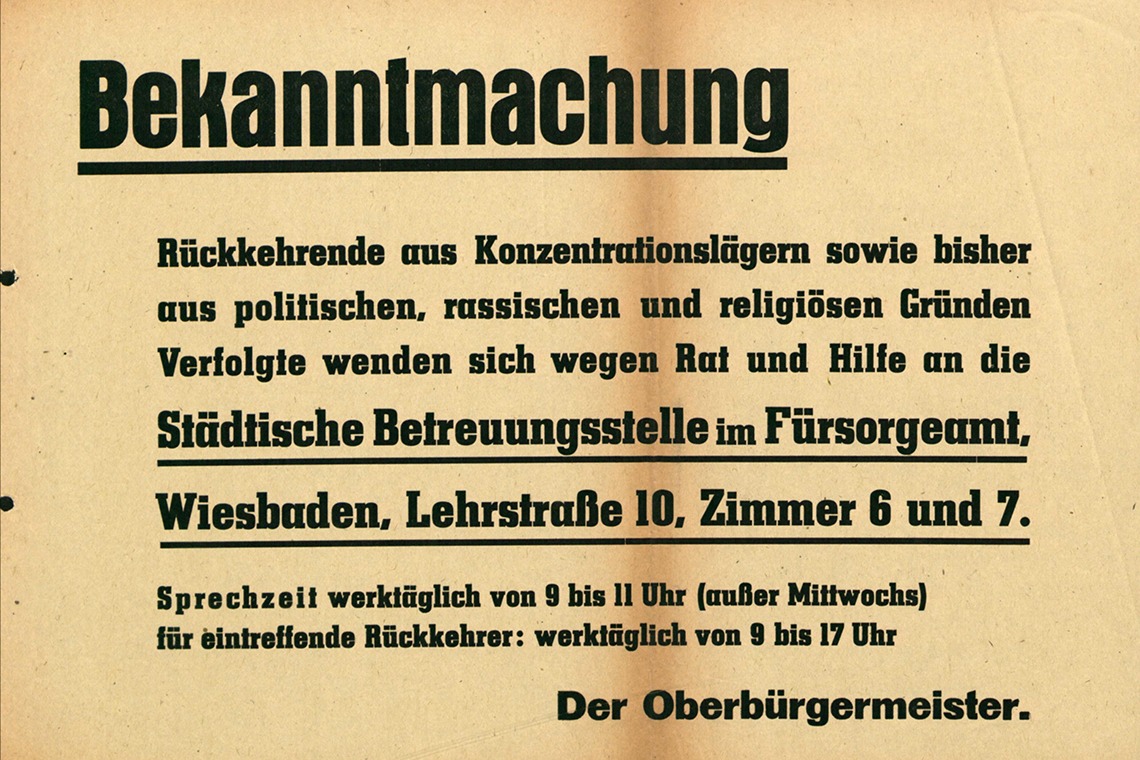

In a small newspaper advertisement, the Community announced the restart of activities at Geisbergstrasse 24.

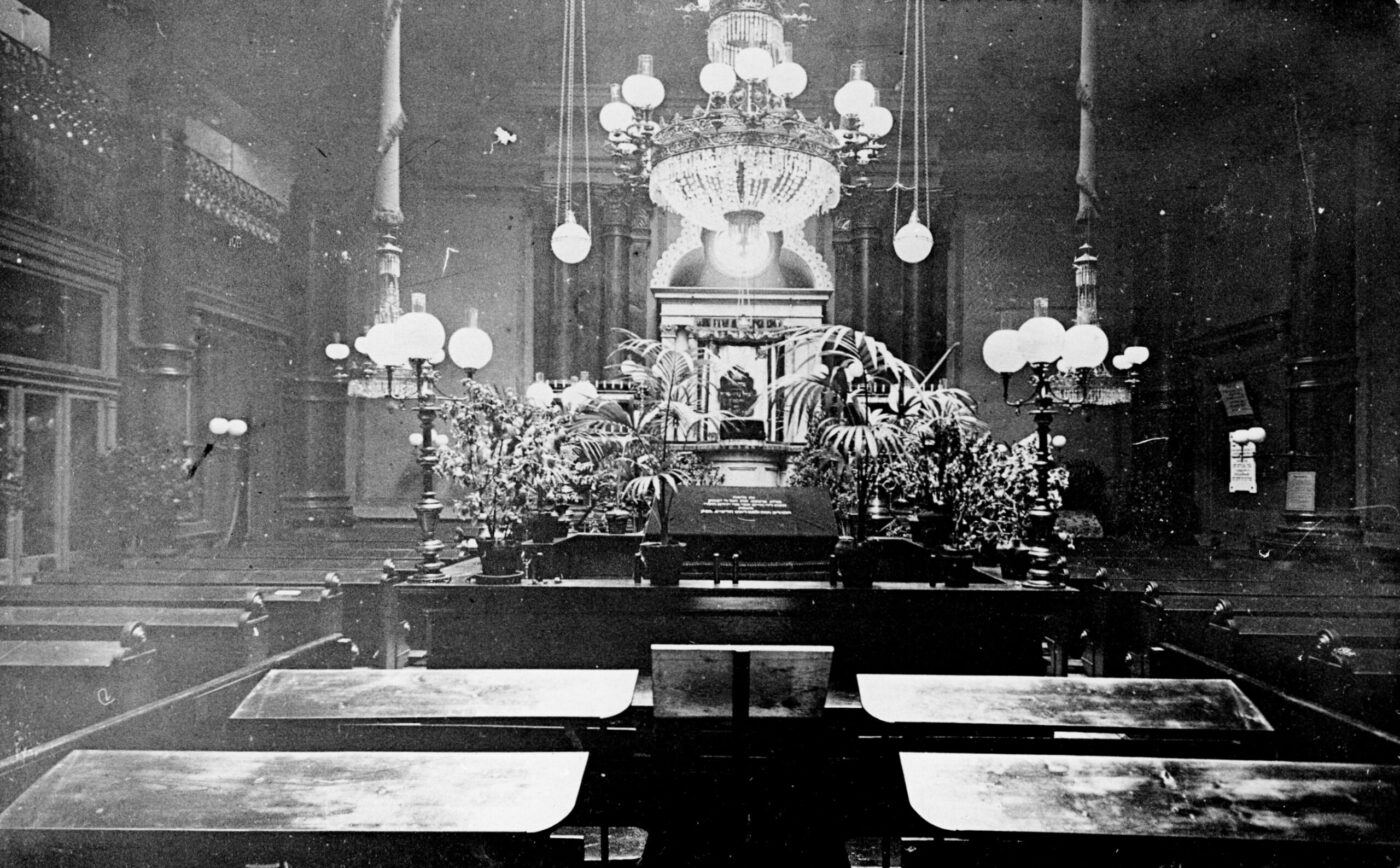

Rededication of the synagogue in Friedrichstraße on the fifth day of Hanukkah.

On July 26, 1945, the Jewish Community Wiesbaden declared the resumption of its business at Geisbergstraße 24. The re-establishment, also from a religious point of view, took place on December 22, 1946. One of the greatest challenges for the first board of directors was to provide for the displaced persons.

On July 21, 1945, Rudolph Jesinghaus, head of the Municipal Care Center for the Politically, Racially and Religiously Persecuted in Wiesbaden, informed Lt. Boardman, head of the Displaced Persons Department of the American military government, that the Wiesbaden Jewish Community had re-established itself and wished to begin its cultural work. Jesinghaus asked Boardman for the necessary permission to do so, which was granted only a few days later. On July 26, the community declared in a small newspaper advertisement that it would resume its business at Geisbergstraße 24.

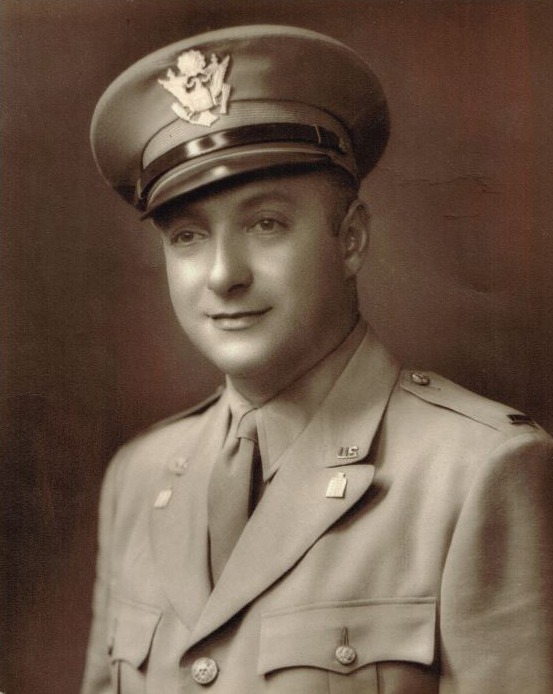

The official re-establishment, also from a religious standpoint, took place on Sunday, December 22, 1946, the fifth day of Hanukkah. On that day, the synagogue on Friedrichstraße was rededicated. Instrumental in this was Rabbi William Z. Dalin, United States Army Air Corps Chaplain. Without his tireless work and his personal and financial commitment, the repair of the desecrated and neglected building would not have been possible Without him, an active Jewish community would not have re-emerged, if at all, until much later. In December 1946, the Jewish Community of Wiesbaden had about 300 members. As reported by the Wiesbadener Kurier, 13 years earlier there had been 3,000 members. At the time of the synagogue’s rededication in 1946, the last major deportation of Wiesbaden Jews had been just four years earlier.

The first board of directors is elected and structures are created

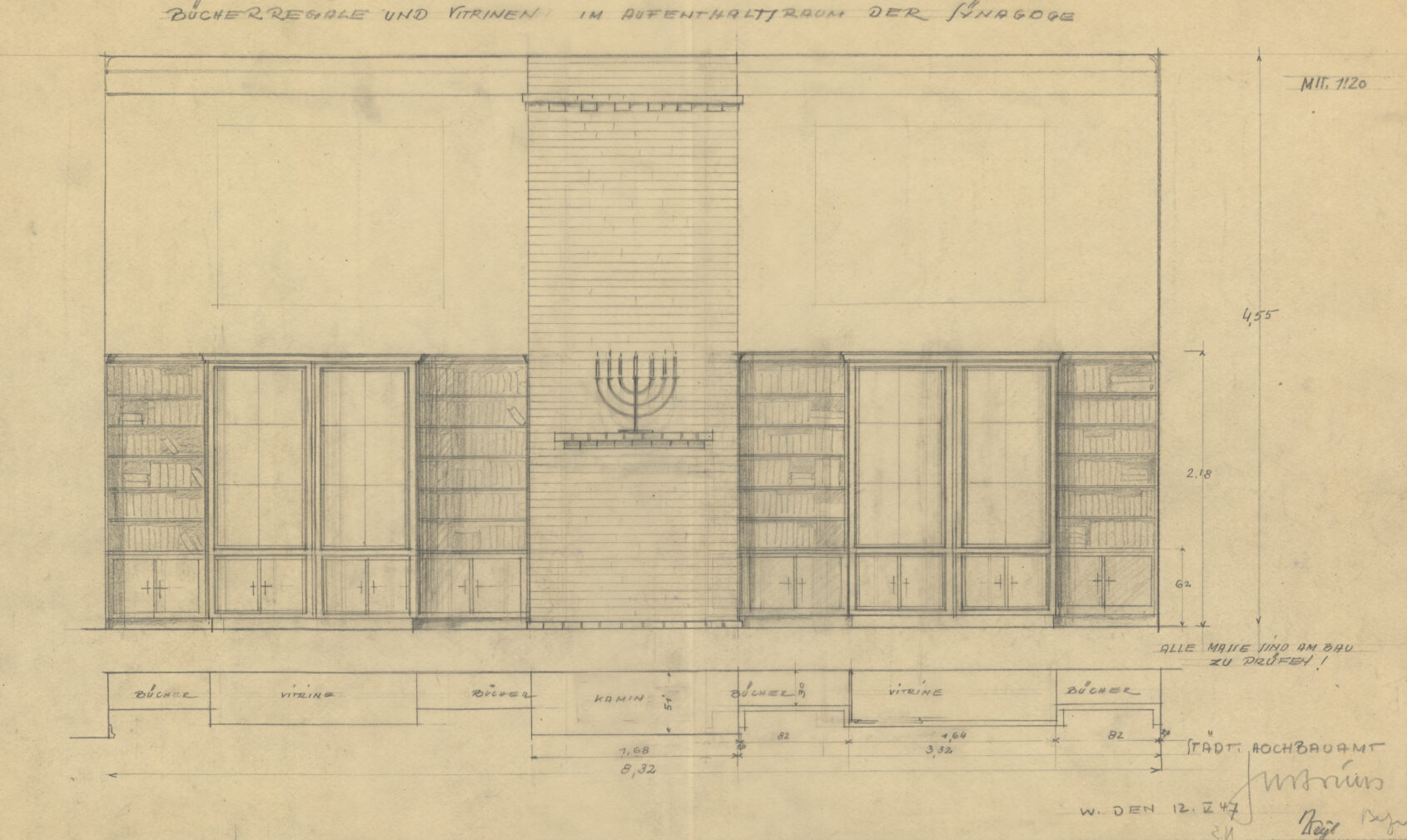

In Wiesbaden, one third of which had been destroyed by the bombing, it was possible from 1946 onwards – with the support of the Americans – to re-establish what the Nazi regime had wanted to destroy: Jewish life One of the greatest challenges of the first years was to provide for the so-called displaced persons – the Jews who had survived the concentration camps or in hiding. Only a few of them were Wiesbaden residents, because the confrontation with their former neighborhood – with a society full of perpetrators who had enriched themselves from the property of Jewish families – was burdensome. Most of the displaced persons stranded in Wiesbaden had only one wish: to emigrate to Palestine. Some eventually remained in Wiesbaden, so that an active community could develop In order to support the severely traumatized people and to be able to rebuild the community, structures had to be created. The first official election of a board of directors took place in January 1946. On January 11, the Frankfurter Rundschau reported that a community board was elected at the first general meeting of the Wiesbaden Jewish Community. Its members until 1947 were: Dr. Leon Frim (president), Jakob Matzner (secretary) and Dr. Baruch Laufer as well as Rabbi Chajim Hecht (directors). The community board acted not only internally, but also as representatives of the community externally. For example, it represented compensation claims against the city concerning the two synagogue properties on Schulberg and Friedrichstraße. A tough struggle for financial support began. The Wiesbadener Kurier wrote about this on December 21, 1946, one day before the rededication of the synagogue on Friedrichstraße: “The almost 300 souls of the community […] are proud to have repaired the first house of worship on their own initiative. Otherwise, they would certainly not have reached their goal. For as much as there has been talk about reparations, so little has happened.” In addition to all these challenges, the Jewish Community was the point of contact for Jews abroad. Jakob Matzner, a member of the community’s board of directors, represented the interests of Jews who had emigrated or been expelled in compensation proceedings connected to Wiesbaden. Magister Estrin, another member of the board, was responsible for culture. Already a year and a half after resuming its business, the congregation, together with Rabbi Dalin, organized a concert with its own orchestra on February 18, 1947, as reported in the magazine “Unterwegs”. The title of the magazine describes the state of the Jewish community. The orchestra was conducted by the Matzner brothers. In addition, Hebrew and English courses were already held regularly, as well as lectures on various current topics. With the help of Rabbi Dalin, the Jewish Community had been able to re-establish a club room and library for its members in the building adjacent to the synagogue on Friedrichstraße. A Purim ball was held in the club room in 1947. Opening with the American national anthem, there followed speeches by Rabbi Dalin, Dr. Frim and Magister Estrin, among others. The formal dinner was followed by a concert by the community choir, led by pianist Irena Steinberg.

“Voices of the Holocaust.”

Leon Frim and Jakob Matzner left a special contemporary document. They responded to the request of psychology professor David Pablo Boder and told him about what they had experienced during the Shoah as part of his “European Displaced Persons Project”. They also told him about their new beginning in Wiesbaden. The goal of the research project was to explore the psychological consequences of the war. Boder conducted 130 interviews with Jews in France, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. He also interviewed non-Jewish individuals. Although his project received no scholarly attention and his publication sold poorly, he created a unique contemporary document with the interviews. The tape recordings were digitized and made available online by the Paul V. Galvin Library, Chicago, under the title “Voices of the Holocaust.” David P. Boder died in Los Angeles in 1961.

To the interview with Leon Frim: https://voices.library.iit.edu/interview/frimL

To the interview with Jakob Matzner: https://voices.library.iit.edu/interview/matznerJ